Further information: History of Palestine, Pre-history of the Southern Levant, History of the Southern Levant, and History of the Levant

The Iron Age kingdom of Israel (blue) and kingdom of Judah (tan), with their neighbours (8th century BC)

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Jews and Judaism |

|---|

|

| Who is a Jew? · Etymology · Culture |

Contents[hide] |

Periods and chronology

Sources

| This section requires expansion. |

The Hebrew Bible contains "myths, legends and folktales, sagas, heroic epics, oral traditions, annals, biographies, narrative histories, novellae, belles lettres, proverbs and wisdom-sayings, poetry (including erotic poems ...), prophecy, apocalyptic, and much more ... the whole finally woven into a composite, highly complex literary fabric sometime in the Hellenistic era."[1] Although Jewish tradition ascribes the biblical books to times and authors contemporaneous with events, they were in fact written in many cases considerably after the times they describe and by authors with a clear religious and nationalist agenda, and it is therefore critical to treat them with circumspection.[2]

On the other hand, "were we entirely dependent on the archaeological evidence narrowly defined, we would not even know that ancient Israel existed"; for this reason archaeology must be interpreted in the light of the Old Testament and the epigraphic evidence.[3]

Late Bronze Age

The eastern Mediterranean seaboard – the Levant – stretches 400 miles north to south from the Taurus Mountains to the Sinai desert, and 70 to 100 miles east to west between the sea and the Arabian desert.[4] The coastal plain of the southern Levant, broad in the south and narrowing to the north, is backed in its southernmost portion by a zone of foothills, the Shephalah; like the plain this narrows as it goes northwards, ending in the promontory of Mount Carmel. East of the plain and the Shephalah is a mountainous ridge, the "hill country of Judah" in the south, the "hill country of Ephraim" north of that, then Galilee and the Lebanon mountains. To the east again lie the steep-sided valley occupied by the Jordan River, the Dead Sea, and the wadi of the Arabah, which continues down to the eastern arm of the Red Sea. Beyond the plateau is the Syrian desert, separating the Levant from Mesopotamia. To the southwest is Egypt, to the northeast Mesopotamia. "The Levant thus constitutes a narrow corridor whose geographical setting made it a constant area of contention between more powerful entities".[5]

Canaan in the Late Bronze Age was a shadow of what it had been centuries earlier: many cities were abandoned, others shrank in size, and the total settled population was probably not much more than a hundred thousand.[6] Settlement was concentrated in cities along the coastal plain and along major communication routes; the central and northern hill country which would later become the biblical kingdom of Israel was only sparsely inhabited[7] although letters from the Egyptian archives indicate that Jerusalem was already a Canaanite city-state recognising Egyptian overlordship.[8] Politically and culturally it was dominated by Egypt,[9] each city under its own ruler, constantly at odds with its neighbours, and appealing to the Egyptians to adjudicate their differences.[7]

The Canaanite city-state system broke down at the end of the Late Bronze period,[10] and Canaanite culture was then gradually absorbed into that of the Philistines, Phoenicians and Israelites.[11] The process was gradual rather than swift:[12] a strong Egyptian presence continued into the 12th century BCE, and, while some Canaanite cities were destroyed, others continued to exist in Iron I.[13]

Iron Age I

The name Israel first appears in the stele of the Egyptian pharaoh Merneptah c. 1209 BCE, "Israel is laid waste and his seed is not."[14] William Dever sees this "Israel" as a cultural and probably political entity of the central highlands, well enough established to be perceived by the Egyptians as a possible challenge to their hegemony, but an ethnic group rather than an organised state.[15] Archaeologist Paula McNutt says: "It is probably ... during Iron Age I [that] a population began to identify itself as 'Israelite'," differentiating itself from its neighbours via prohibitions on intermarriage, an emphasis on family history and genealogy, and religion.[16]

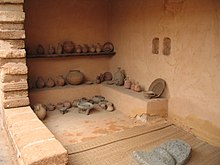

On the basis of extensive surface surveys, the number of villages in the highlands is estimated to have increased from 25 in the Late Bronze Age to over 300 by the end of Iron I, while the settled population doubled from 20,000 in the 11th century to 40,000 in the 12th.[17] The villages, more and larger in the north, probably shared the highlands with other communities like pastoral nomads that left no remains.[18] Archaeologists and historians see more continuity than discontinuity between Iron Age highlanders and Late Bronze Canaanites:[19] features that have been said to be specifically Israelite – notably collared-rim jars and four-room houses, have now been identified outside the highlands and thus cannot be used to distinguish Israelite sites;[20] and, while highland villages display a far more limited late–13th–century BCE ceramic repertoire than that of lowland Canaanite sites, it develops typologically out of Canaanite pottery that came before.[21] Israel Finkelstein proposed that the oval or circular layout that distinguishes highland sites and the notable absence of pig bones from hill sites can be taken as a marker of ethnicity, but others have cautioned that these can be a "common-sense" adaptation to highland life and not necessarily revelatory of origins.[22]

In the early 20th century three models emerged to explain the origin of these Israelites: the "conquest" model which essentially affirmed the historicity of the biblical narrative, the "peaceful infiltration" model which saw the Israelites as nomads who entered and settled the highlands over a long period, and the "peasants revolt" model which proposed that the early Israelites were a Canaanite underclass in revolt against their overlords.[23] All three have been criticised extensively, and modern scholars see Israel arising peacefully and internally in the highlands.[24]

Iron Age II

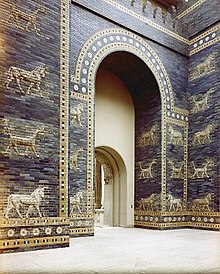

Unusually favourable climatic conditions in the first two centuries of Iron Age II brought about an expansion of population, settlements and trade throughout the region.[25] In the central highlands this resulted in unification in a kingdom with the city of Samaria as its capital,[25] possibly by the second half of the 10th century BCE when an inscription of the Egyptian pharaoh Shoshenq I, the biblical Shishak, records a series of campaigns directed at the area.[26] It had clearly emerged by the middle of the 9th century BCE, when the Assyrian king Shalmaneser III names "Ahab the Israelite" among his enemies at the battle of Qarqar (853), and the Mesha stele (c. 830) left by a king of Moab celebrates his success in throwing off the oppression of the "House of Omri" (i.e. Israel) and the Tel Dan stele tells of the death of a king of Israel, probably Jehoram, at the hands of an Aramaen king (c. 841).[26] In the earlier part of this period Israel was apparently engaged in a three-way contest with Damascus and Tyre for control of the Jezreel Valley and Galilee in the north, and with Moab, Ammon and Damascus in the east for control of Gilead;[25] from the middle of the 8th century BCE it came into increasing conflict with the expanding neo-Assyrian empire, which first split its territory into several smaller units and then destroyed its capital, Samaria (722). Both the biblical and Assyrian sources speak of a massive deportation of the people of Israel and their replacement with an equally large number of forced settlers from other parts of the empire – such population exchanges were an established part of Assyrian imperial policy, a means of breaking the old power structure. The former Israel never again became an independent political entity.[27]

Surface surveys indicate that during the 10th and 9th centuries BCE the southern highlands were divided between a number of centres, none with clear primacy.[28] Unification (i.e., state formation) seems to have occurred no earlier than the 9th century BCE, a period when Jerusalem was dominated by Israel, but the subject is the centre of considerable controversy and there is no definite answer to the question of when Judah emerged.[29] In the 7th century BCE Jerusalem became a city with a population many times greater than before and clear dominance over its neighbours, probably in a cooperative arrangement with the Assyrians to establish Judah as a pro-Assyrian vassal state controlling the valuable olive industry.[30] Judah prospered under Assyrian vassalage (despite a disastrous rebellion against the Assyrian king Sennacherib), but in the last half of the 7th century BCE Assyria suddenly collapsed, and the ensuing competition between the Egyptian and Neo-Babylonian empires for control of Palestine led to the destruction of Judah in a series of campaigns between 597 and 582.[30]

Babylonian period

Babylonian Judah suffered a steep decline in both economy and population[31] and lost the Negev, the Shephelah, and part of the Judean hill country, including Hebron, to encroachments from Edom and other neighbours.[32] Jerusalem, while probably not totally abandoned, was much smaller than previously, and the town of Mizpah in Benjamin in the relatively unscathed northern section of the kingdom became the capital of the new Babylonian province of Yehud Medinata.[33] (This was standard Babylonian practice: when the Philistine city of Ashkalon was conquered in 604, the political, religious and economic elite (but not the bulk of the population) was banished and the administrative centre shifted to a new location).[34] There is also a strong probability that for most or all of the period the temple at Bethel in Benjamin replaced that at Jerusalem, boosting the prestige of Bethel's priests (the Aaronites) against those of Jerusalem (the Zadokites), now in exile in Babylon.[35]

The Babylonian conquest entailed not just the destruction of Jerusalem and its temple, but the liquidation of the entire infrastructure which had sustained Judah for centuries.[36] The most significant casualty was the State ideology of "Zion theology,"[37] the idea that the God of Israel had chosen Jerusalem for his dwelling-place and that the Davidic dynasty would reign there forever.[38] The fall of the city and the end of Davidic kingship forced the leaders of the exile community – kings, priests, scribes and prophets – to reformulate the concepts of community, faith and politics.[39] The exile community in Babylon thus became the source of significant portions of the Hebrew Bible: Isaiah 40–55, Ezekiel, the final version of Jeremiah, the work of the Priestly source in the Pentateuch, and the final form of the history of Israel from Deuteronomy to 2 Kings[40] Theologically, they were responsible for the doctrines of individual responsibility and universalism (the concept that one god controls the entire world), and for the increased emphasis on purity and holiness.[40] Most significantly, the trauma of the exile experience led to the development of a strong sense of identity as a people distinct from other peoples,[41] and increased emphasis on symbols such as circumcision and Sabbath-observance to maintain that separation.[42]

The concentration of the biblical literature on the experience of the exiles in Babylon disguises the fact that the great majority of the population remained in Judah, and for them life after the fall of Jerusalem probably went on much as it had before.[43] It may even have improved, as they were rewarded with the land and property of the deportees, much to the anger of the exile community in Babylon.[44] The assassination of the Babylonian governor around 582 by a disaffected member of the former royal house of David provoked a Babylonian crackdown, possibly reflected in the Book of Lamentations, but the situation seems to have soon stabilised again.[45] Nevertheless, the unwalled cities and towns that remained were subject to slave raids by the Phoenicians and intervention in their internal affairs from Samaritans, Arabs and Ammonites.[46]

Persian period

Main article: Yehud Medinata

When Babylon fell to the Persian Cyrus the Great in 539 BCE, Judah (or Yehud medinata, the "province of Yehud") became a province of the Persian empire until 332 BCE. Cyrus was succeeded as king by Cambyses, who added Egypt to the empire, incidentally transforming Yehud and the Philistine plain into an important frontier zone. His death in 522 was followed by a period of turmoil until Darius the Great seized the throne in about 521. Darius introduced a reform of the administrative arrangements of the empire including the collection, codification and administration of local law codes, and it is reasonable to suppose that this policy lay behind the redaction of the Jewish Torah.[47] After 404 the Persians lost control of Egypt, which became Persia's main rival outside Europe, causing the Persian authorities to tighten their administrative control over Yehud and the rest of the Levant.[48] Egypt was eventually reconquered, but soon afterward Persia fell to Alexander the Great, ushering in the Hellenistic period in the Levant.Yehud's population over the entire period was probably never more than about 30,000, and that of Jerusalem no more than about 1,500, most of them connected in some way to the Temple.[49] According to the biblical history, one of the first acts of Cyrus, the Persian conqueror of Babylon, was to commission the Jewish exiles to return to Jerusalem and rebuild the Temple, a task which they are said to have completed c. 515.[50] Yet it was probably only in the middle of the next century, at the earliest, that Jerusalem again became the capital of Judah.[51] The Persians may have experimented initially with ruling Yehud as a Dividic client-kingdom under descendants of Jehoiachin,[52] but by the mid–5th century BCE Yehud had become in practice a theocracy, ruled by hereditary High Priests[53] and a Persian-appointed governor, frequently Jewish, charged with keeping order and seeing that tribute was paid.[54] According to the biblical history Ezra and Nehemiah arrived in Jerusalem in the middle of the 5th century BCE, the first empowered by the Persian king to enforce the Torah, the second with the status of governor and a royal mission to restore the walls of the city.[55] The biblical history mentions tension between the returnees and those who had remained in Yehud, the former rebuffing the attempt of the "peoples of the land" to participate in the rebuilding of the Temple; this attitude was based partly on the exclusivism which the exiles had developed while in Babylon and, probably, partly on disputes over property.[56] The careers of Ezra and Nehemiah in the 5th century BCE were thus a kind of religious colonisation in reverse, an attempt by one of the many Jewish factions in Babylon to create a self-segregated, ritually pure society inspired by the prophesies of Ezekiel and his followers.[57]

The Persian era, and especially the period 538–400, laid the foundations of later Jewish and Christian religion and the beginnings of a scriptural canon.[58] other important landmarks include the replacement of Hebrew by Aramaic as the everyday language of Judah (although it continued to be used for religious and literary purposes),[59] and Darius's reform of the administrative arrangements of the empire, which may lie behind the redaction of the Jewish Torah.[47] The Israel of the Persian period included descendants of the inhabitants of the old kingdom of Judah, returnees from the Babylonian exile community, Mesopotamians who had joined them or had been exiled themselves to Samaria at a far earlier period, Samaritans and others.[60]

Hellenistic period

On the death of Alexander the Great (322) his generals divided the empire between them. Ptolemy I, the ruler of Egypt, seized Palestine, but his successors lost it to the Seleucids of Syria in 198. At first relations between the Seleucids and the Jews were cordial, but the attempt of Antiochus IV Epiphanes (174–163) to impose Hellenic culture sparked a national rebellion, which ended in the expulsion of the Syrians and the establishment of an independent Jewish kingdom under the Hasmonean dynasty. The Hasmonean kingdom was a conscious attempt to revive the Judah described in the Bible: a Jewish monarchy ruled from Jerusalem and stretching over all the territories once ruled by David and Solomon. In order to carry out this project the Hasmoneans forcibly converted to Judaism the one-time Moabites, Edomites and Ammonites, as well as the lost kingdom of Israel.[61]

In 63 BCE the Roman general Pompey conquered Jerusalem and made the Jewish kingdom a client of Rome. In 40–39, Herod the Great was appointed King of the Jews by the Roman Senate, and in 6 CE the last ethnarch of Judea was deposed by the emperor Augustus and his territories were combined with Idumea and Samaria and annexed as Iudaea Province under direct Roman administration.[62] The name Judea (Iudaea) was removed after the revolt of Simon Bar Kochba in 135 CE, after which the area was called Syria Palaestina, (Greek: Παλαιστίνη, Palaistinē; Latin: Palaestina.

Religion

Iron Age Yahwism

Further information: Yahweh (Canaanite deity) and El (god)

Current models among scholars see the emergence of Israelite monotheism as a gradual process which began with the normal beliefs and practices of the ancient world.[63]The religion of the Israelites of Iron Age I was based on the cult of the ancestors and the worship of family gods (the "gods of the fathers").[64] The major deities were not numerous – El, Asherah, and Yahweh, with Baal as a fourth god in the early period.[65] By the early monarchy El and Yahweh had become identified and Asherah did not continue as a separate state cult,[65] although she continued to be popular at a community level until Persian times.[66] Yahweh, later the national god of both Israel and Judah seems to have originated in Edom and Midian in southern Canaan, and may have been brought north to Israel by the Kenites and Midianites at an early stage.[67] With the emergence of monarchy at the beginning of Iron Age II the king promoted his own family god, Yahweh, as the god of the kingdom, but beyond the royal court religion continued to be both polytheistic and family-centered, as it was also for other societies in the Ancient Near East.[68]

There is a general consensus among scholars that the first formative event in the emergence of the distinctive religion described in the bible was triggered by the destruction of Israel by Assyria in c.722 BCE. Refugees came south to Judah, bringing with them laws and a Prophetic tradition that Yahweh was the only god who should be served. These beliefs were adopted by the "people of the land", meaning the landed families who provided the administrative class of the kingdom, and in 640 BCE these circles were decisive in placing on the throne the eight-year-old Josiah. Judah at this time was a vassal of Assyria, but Assyrian power collapsed in the 630s, and in around 622 Josiah and the Deuteronomists, as the circle around him are called by modern scholars, launched a bid for independence expressed as loyalty to "Yahweh alone" and the law-code in the book of Deuteronomy, written in the form of a treaty between Judah and Yahweh to replace the vassal-treaty with Assyria.[69]

According to the theology of the Deuteronomists the terms of the treaty with Yahweh were that he would preserve both the city and the king in return for their worship and obedience to the law-code. The destruction of Jerusalem, the Temple, and the Davidic dynasty by Babylon in 587/586 BCE was therefore a deeply traumatic event, and led to much theological reflection on the meaning of the national tragedy. The solution, set out in the series of history books from Joshua and Judges to Samuel and Kings, was to interpret the Babylonian destruction as divinely-ordained punishment for the failure of the kings to worship Yahweh alone.[70]

Second Temple Judaism

The Second Temple period (520BC-70AD) differed in significant ways from what had gone before. [71] Monotheism had emerged among the priests and the Temple establishment probably by the beginning of the Persian period, and beliefs regarding angels and demons were developing rapidly by the its end.[72] It was at this time that the Torah was written, circumcision and Sabbath-observance became symbols of Jewish identity, and the institution of the synagogue became increasingly important.[73] By the end of the Second Temple period the Jewish canon was becoming fixed, and, since there was still no monarchy and the reality of life did not match the expectations created by the religious traditions, messianic expectation began to surface.[74]See also

|

References

- ^ Dever 2001, p. 2.

- ^ Golden 2004b, pp. 62–3.

- ^ Miller in Mayes et al, p. 257

- ^ Miller 1986, p. 36.

- ^ Coogan 1998, pp. 4–7.

- ^ Finkelstein 2001, p. 78.

- ^ a b Killebrew 2005, pp. 38–9.

- ^ Cahill in Vaughn 1992, pp. 27–33.

- ^ Kuhrt 1995, p. 317.

- ^ Killebrew 2005, pp. 10–6.

- ^ Golden 2004b, pp. 61–2.

- ^ McNutt 1999, p. 47.

- ^ Golden 2004a, p. 155.

- ^ Stager in Coogan 1998, p. 91.

- ^ Dever 2003, p. 206.

- ^ McNutt 1999, pp. 35.

- ^ McNutt 1999, pp.46-47.

- ^ McNutt 1999, p. 69.

- ^ Bright 2000, p. 472.

- ^ Miller 1986, p. 72.

- ^ Killebrew 2005, p. 13.

- ^ Edelman in Brett 2002, p. 46-47.

- ^ Pitkänen 2004, pp. 161–5.

- ^ Gnuse 1997, pp.28,31

- ^ a b c Thompson 1992, p. 408.

- ^ a b Mazar in Finkelstein 2007, p. 163.

- ^ Lemche 1998, p. 85.

- ^ Lehman in Vaughn 1992, p. 149.

- ^ Grabbe 2008, pp. 225–6.

- ^ a b Thompson 1992, pp. 410–1.

- ^ Grabbe 2004, p. 28.

- ^ Lemaire in Blenkinsopp 2003, p. 291.

- ^ Davies 2009.

- ^ Lipschits 2005, p. 48.

- ^ Blenkinsopp in Blenkinsopp 2003, pp. 103–5.

- ^ Blenkinsopp 2009, p. 228.

- ^ Middlemas 2005, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Miller 1986, p. 203.

- ^ Middlemas 2005, p. 2.

- ^ a b Middlemas 2005, p. 10.

- ^ Middlemas 2005, p. 17.

- ^ Bedford 2001, p. 48.

- ^ Barstad 2008, p. 109.

- ^ Albertz 2003a, p. 92.

- ^ Albertz 2003a, pp. 95–6.

- ^ Albertz 2003a, p. 96.

- ^ a b Blenkinsopp 1988, p. 64.

- ^ Lipschits in Lipschits 2006, pp. 86–9.

- ^ Grabbe 2004, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Nodet 1999, p. 25.

- ^ Davies in Amit 2006, p. 141.

- ^ Niehr in Becking 1999, p. 231.

- ^ Wylen 1996, p. 25.

- ^ Grabbe 2004, pp. 154–5.

- ^ Soggin 1998, p. 311.

- ^ Miller 1986, p. 458.

- ^ Blenkinsopp 2009, p. 229.

- ^ Albertz 1994, pp. 437–8.

- ^ Kottsieper in Lipschits 2006, pp. 109–10.

- ^ Becking in Albertz 2003b, p. 19.

- ^ Davies 1992, pp. 149–50.

- ^ Ben-Sasson 1976, p. 246.

- ^ Gnuse 1997, pp. 62–3.

- ^ Van der Toorn 1996, p.4.

- ^ a b Smith 2002, p. 57.

- ^ "Dever, William G. (2005), "Did God Have a Wife; Archaeology And Folk Religion In Ancient Israel" (Erdmanns)

- ^ Van der Toorn 1999, p. 911–3.

- ^ Van der Toorn 1996, p. 181–2.

- ^ Dunn and Rogerson, pp.153–154

- ^ Dunn and Rogerson, pp.153–154

- ^ Avery Peck, p.58

- ^ Grabbe (2004), pp. 243-244

- ^ Avery Peck, p.59

- ^ Avery Peck, p.59

Bibliography

- Albertz, Rainer (1994) [Vanderhoek & Ruprecht 1992]. A History of Israelite Religion, Volume I: From the Beginnings to the End of the Monarchy. Westminster John Knox Press.

- Albertz, Rainer (1994) [Vanderhoek & Ruprecht 1992]. A History of Israelite Religion, Volume II: From the Exile to the Maccabees. Westminster John Knox Press.

- Albertz, Rainer (2003a). Israel in Exile: The History and Literature of the Sixth Century B.C.E.. Society of Biblical Literature.

- Albertz, Rainer; Becking, Bob, eds. (2003b). Yahwism After the Exile: Perspectives on Israelite Religion in the Persian Era. Koninklijke Van Gorcum. Becking, Bob. "Law as Expression of Religion (Ezra 7–10)".

- Amit, Yaira, et al., eds. (2006). Essays on Ancient Israel in its Near Eastern Context: A Tribute to Nadav Na'aman. Eisenbrauns. Davies, Philip R. "The Origin of Biblical Israel".

- Avery-Peck, Alan, et al., eds. (2003). The Blackwell Companion to Judaism. Blackwell. Murphy, Frederick J. R. "Second Temple Judaism".

- Barstad, Hans M. (2008). History and the Hebrew Bible. Mohr Siebeck.

- Becking, Bob, ed. (2001). Only One God? Monotheism in Ancient Israel and the Veneration of the Goddess Asherah. Sheffield Academic Press. Dijkstra, Meindert. "El the God of Israel, Israel the People of YHWH: On the Origins of Ancient Israelite Yahwism". Dijkstra, Meindert. "I Have Blessed You by Yahweh of Samaria and His Asherah: Texts with Religious Elements from the Soil Archive of Ancient Israel".

- Becking, Bob; Korpel, Marjo Christina Annette, eds. (1999). The Crisis of Israelite Religion: Transformation of Religious Tradition in Exilic and Post-Exilic Times. Brill. Niehr, Herbert. Religio-Historical Aspects of the Early Post-Exilic Period.

- Bedford, Peter Ross (2001). Temple Restoration in Early Achaemenid Judah. Brill.

- Ben-Sasson, H.H. (1976). A History of the Jewish People. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674397312.

- Blenkinsopp, Joseph (1988). Ezra-Nehemiah: A Commentary. Eerdmans.

- Blenkinsopp, Joseph; Lipschits, Oded, eds. (2003). Judah and the Judeans in the Neo-Babylonian Period. Eisenbrauns. Blenkinsopp, Joseph. "Bethel in the Neo-Babylonian Period". Lemaire, Andre. "Nabonidus in Arabia and Judea During the Neo-Babylonian Period".

- Blenkinsopp, Joseph (2009). Judaism, the First Phase: The Place of Ezra and Nehemiah in the Origins of Judaism. Eerdmans.

- Brett, Mark G. (2002). Ethnicity and the Bible. Brill. Edelman, Diana. "Ethnicity and Early Israel".

- Bright, John (2000; 4th ed., 1st ed. 1959). A History of Israel. Westminster John Knox Press.

- Coogan, Michael D., ed. (1998). The Oxford History of the Biblical World. Oxford University Press. Stager, Lawrence E. "Forging an Identity: The Emergence of Ancient Israel".

- Coogan, Michael D. (2009). A Brief Introduction to the Old Testament. Oxford University Press.

- Coote, Robert B.; Whitelam, Keith W. (1986). "The Emergence of Israel: Social Transformation and State Formation Following the Decline in Late Bronze Age Trade". Semeia (37): 107–47.

- Davies, Philip R. (1992). In Search of Ancient Israel. Sheffield.

- Davies, Philip R. (2009). "The Origin of Biblical Israel". Journal of Hebrew Scriptures 9 (47).

- Day, John (2002). Yahweh and the Gods and Goddesses of Canaan. Sheffield Academic Press.

- Dever, William (2001). What Did the Biblical Writers Know, and When Did They Know It?. Eerdmans.

- Dever, William (2003). Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come From?. Eerdmans.

- Dever, William (2005). Did God Have a Wife?: Archaeology and Folk Religion in Ancient Israel. Eerdmans.

- Dunn, James D.G; Rogerson, John William, eds. (2003). Eerdmans commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. Rogerson, John William. "Deuteronomy".

- Edelman, Diana, ed. (1995). The Triumph of Elohim: From Yahwisms to Judaisms. Kok Pharos.

- Finkelstein, Neil Asher; Silberman (2001). The Bible Unearthed.

- Finkelstein, Israel; Mazar, Amihay; Schmidt, Brian B. (2007). The Quest for the Historical Israel. Society of Biblical Literature. Mazar, Amihay. "The Divided Monarchy: Comments on Some Archaeological Issues".

- Gnuse, Robert Karl (1997). No Other Gods: Emergent Monotheism in Israel. Sheffield Academic Press.

- Golden, Jonathan Michael (2004a). Ancient Canaan and Israel: An Introduction. Oxford University Press.

- Golden, Jonathan Michael (2004b). Ancient Canaan and Israel: New Perspectives. ABC-CLIO.

- Goodison, Lucy; Morris, Christine (1998). Goddesses in Early Israelite Religion in Ancient Goddesses: The Myths and the Evidence. University of Wisconsin Press.

- Grabbe, Lester L. (2004). A History of the Jews and Judaism in the Second Temple Period. T&T Clark International.

- Grabbe, Lester L., ed. (2008). Israel in Transition: From Late Bronze II to Iron IIa (c. 1250–850 B.C.E.). T&T Clark International.

- Killebrew, Ann E. (2005). Biblical Peoples and Ethnicity: An Archaeological Study of Egyptians, Canaanites, and Early Israel, 1300–1100 B.C.E.. Society of Biblical Literature.

- King, Philip J.; Stager, Lawrence E. (2001). Life in Biblical Israel. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 0664221483.

- Kuhrt, Amélie (1995). The Ancient Near East c. 3000–330 BC. Routledge.

- Lemche, Niels Peter (1998). The Israelites in History and Tradition. Westminster John Knox Press.

- Levy, Thomas E. (1998). The Archaeology of Society in the Holy Land. Continuum International Publishing. LaBianca, Øystein S.; Younker, Randall W. "The Kingdoms of Ammon, Moab and Edom: The Archaeology of Society in Late Bronze/Iron Age Transjordan (c. 1400–500 CE)".

- Lipschits, Oded (2005). The Fall and Rise of Jerusalem. Eisenbrauns.

- Lipschits, Oded, et al., eds. (2006). Judah and the Judeans in the Fourth Century B.C.E.. Eisenbrauns. Kottsieper, Ingo. "And They Did Not Care to Speak Yehudit". Lipschits, Oded; Vanderhooft, David. "Yehud Stamp Impressions in the Fourth Century B.C.E.".

- Liverani, Mario (2005). Israel's History and the History of Israel, London, Equinox.

- Markoe, Glenn (2000). Phoenicians. University of California Press.

- Mays, James Luther, et al., eds. (1995). Old Testament Interpretation. T&T Clarke. Miller, J. Maxwell. "The Middle East and Archaeology".

- McNutt, Paula (1999). Reconstructing the Society of Ancient Israel. Westminster John Knox Press.

- Merrill, Eugene H. (1995). "The Late Bronze/Early Iron Age Transition and the Emergence of Israel". Bibliotheca Sacra 152 (606): 145–62.

- Middlemas, Jill Anne (2005). The Troubles of Templeless Judah. Oxford University Press.

- Miller, James Maxwell; Hayes, John Haralson (1986). A History of Ancient Israel and Judah. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 066421262X.

- Miller, Robert D. (2005). Chieftains of the Highland Clans: A History of Israel in the 12th and 11th Centuries B.C.. Eerdmans.

- Nodet, Étienne (1999) [Editions du Cerf 1997]. A Search for the Origins of Judaism: From Joshua to the Mishnah. Sheffield Academic Press.

- Pitkänen, Pekka (2004). "Ethnicity, Assimilation and the Israelite Settlement". Tyndale Bulletin 55 (2): 161–82.

- Silberman, Neil Asher; Small, David B., eds. (1997). The Archaeology of Israel: Constructing the Past, Interpreting the Present. Sheffield Academic Press. Hesse, Brian; Wapnish, Paula. "Can Pig Remains Be Used for Ethnic Diagnosis in the Ancient Near East?".

- Smith, Mark S. (2001). Untold Stories: The Bible and Ugaritic Studies in the Twentieth Century. Hendrickson Publishers.

- Smith, Mark S.; Miller, Patrick D. (2002) [Harper & Row 1990]. The Early History of God. Eerdmans.

- Soggin, Michael J. (1998). An Introduction to the History of Israel and Judah. Paideia.

- Thompson, Thomas L. (1992). Early History of the Israelite People. Brill.

- Van der Toorn, Karel (1996). Family Religion in Babylonia, Syria, and Israel. Brill.

- Van der Toorn, Karel; Becking, Bob; Van der Horst, Pieter Willem (1999). Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible (2d ed.). Koninklijke Brill.

- Vaughn, Andrew G.; Killebrew, Ann E., eds. (1992). Jerusalem in Bible and Archaeology: The First Temple Period. Sheffield. Cahill, Jane M. "Jerusalem at the Time of the United Monarchy". Lehman, Gunnar. "The United Monarchy in the Countryside".

- Wylen, Stephen M. (1996). The Jews in the Time of Jesus: An Introduction. Paulist Press.

- Zevit, Ziony (2001). The Religions of Ancient Israel: A Synthesis of Parallactic Approaches. Continuum.

Further reading

- Avery-Peck, Alan, and Neusner, Jacob, (eds), "The Blackwell Companion to Judaism (Blackwell, 2003)

- Boadt, Lawrence, "Reading the Old Testament: An Introduction" (Paulist Press, 1984)

- Brettler, Marc Zvi, "The Creation of History in Ancient Israel" (Routledge, 1995), and also review at Dannyreviews.com

- Cook, Stephen L., "The social roots of biblical Yahwism" (Society of Biblical Literature, 2004)

- Day, John (ed), "In search of pre-exilic Israel: proceedings of the Oxford Old Testament Seminar" (T&T Clark International, 2004)

- Gravett, Sandra L., "An Introduction to the Hebrew Bible: A Thematic Approach" (Westminster John Knox Press, 2008)

- Grisanti, Michael A., and Howard, David M., (eds), "Giving the Sense:Understanding and Using Old Testament Historical Texts" (Kregel Publications, 2003)

- Hess, Richard S., "Israelite religions: an archaeological and biblical survey" Baker, 2007)

- Kavon, Eli, "Did the Maccabees Betray the Hanukka Revolution?" (The Jerusalem Post, 26 December 2005)

- Lemche, Neils Peter, "The Old Testament between theology and history: a critical survey" (Westminster John Knox Press, 2008)

- Levine, Lee I., "Jerusalem: portrait of the city in the second Temple period (538 B.C.E.–70 C.E.)" (Jewish Publication Society, 2002)

- Na'aman, Nadav, "Ancient Israel and its neighbours" (Eisenbrauns, 2005)

- Penchansky, David, "Twilight of the gods: polytheism in the Hebrew Bible" (Westminster John Knox Press, 2005)

- Provan, Iain William, Long, V. Philips, Longman, Tremper, "A Biblical History of Israel" (Westminster John Knox Press, 2003)

- Russell, Stephen C., "Images of Egypt in early biblical literature" (Walter de Gruyter, 2009)

- Sparks, Kenton L., "Ethnicity and identity in ancient Israel" (Eisenbrauns, 1998)

- Stackert, Jeffrey, "Rewriting the Torah: literary revision in Deuteronomy and the holiness code" (Mohr Siebeck, 2007)

- Vanderkam, James, "An introduction to early Judaism" (Eerdmans, 2001)

- Velazquez, Efrain, "The Persian Period and the Origins of 'Israel': Beyond the Myths", (Bible and Interpretation, July 2009)